I have a problem with the phrase “the patience of Job.” I don’t know who coined it, but reading his self-titled account of misery (arguably the oldest book in the Bible, in spite of its placement), I can’t help thinking that whoever popularized it skipped ahead in the script and overlooked his bitter lines. When I read his story, which I have more than once, I’m left with the distinct impression that the only thing separating Job from your children or mine is that Job simply complains more eloquently about his lot in life.

I’m over-exaggerating, of course. The fact is, I don’t begrudge him his penchant for extensive bellyaching, in which I personally see little of the ascribed virtue of patience. There are few in Scripture who have more of a right to it than Job, in my humble opinion. After all, his suffering was not the result of personal sin, karma, or even chance; nobody to blame there except, maybe, yourself. No, his misfortune was the result of a bet staked between the Creator and the “Accuser.” While this book is among my favorites of the 66, it does feel a bit cold the way his life was essentially employed as a playing field to settle a score. Then again, as Job concluded, who am I to judge? “Surely I [speak] of things I [do] not understand.”

I imagine the virtue of patience is better applied to Job at the end of his ordeal, when he couldn’t possibly experience thereafter anything worse than what we read. Nowhere to go but up. And let’s be honest — it’s tales such as this that prompt us to think twice about asking God for more of this quality, which reminds me of another phrase: “Be careful what you wish for . . .”

Patience serves well those in my profession of public librarianship. Insert the word “public” before your chosen occupation and you’re likely to deal with anything and anyone, with special emphasis on the “anyone.” Moreover, the all-encompassing “public” includes you, me, and that difficult person you do your best to avoid. More often than we’d like, it’s the latter we librarians encounter across the reference desk, and without an extra measure of patience we’d probably finish most days with cuts and bruises, both given and taken.

During my time at the desk, I was given special regard among my colleagues for this quality when interacting with patrons or people in general. I even once was told by a staff person that they would settle when I showed up to handle a tense encounter; I brought calm to a situation, she said, though I seldom felt it. When once I paused to wonder why, it came as no surprise. I was bred, if you will, in relative peace and calm, thanks both to nature and nurture. I can’t recall a moment growing up when my siblings and I ever came to literal blows over anything, though we had our minor spats on occasion. I learned later as an adult, to my surprise, that such domestic tranquility is atypical. Nevertheless, my mother made it her mission to create an environment for us she rarely experienced in her own upbringing. Our consequent peace-loving natures unknowingly cultivated in us a conspicuous patience in our interactions with others, which, for the most part, has served us well in relationships. Patience, it seemed, was as natural to me as any functioning internal organ; whether I thought of it or not, it was somewhere in there and did its job regardless.

Enter children.

If you want to get to know yourself better, have kids. Contrary to popular belief, they don’t enter the world naked. They arrive equipped with a figurative outward-facing mirror designed to reveal to you and your spouse both your best and your worst characteristics.

Calib, our youngest, is still unaware that one of his purposes in life is to refine my patience, to demonstrate to me how little of it I actually possess. It turns out, I’m not quite the paragon of longsuffering that I once thought. He and his oldest sister, Deztinee, entered our lives just over five years ago and their sister, Dezira, a few months after that. As for him, it was clear from the start that this 2-year-old was not informed by the adoption agency that he had to accommodate my idea or manner of expressing patience, much to my consternation. It didn’t take long to discover that I myself had an inner toddler that felt the impulse to rebel when things weren’t going his way.

Our first family pics, only months after placement, were in Alexandria, Louisiana, home to my in-laws. One photo in particular of the two of us currently hangs on his bedroom wall. We were not able to cut his hair yet, per the rules, but we also hadn’t a clue what to do with it in the meantime. He consequently resembled a Don King mini-me, an expression on his face betraying an interest in stirring up mischief. I sit behind him, and it is, admittedly, a cute picture, except that my smile is forced, which only my wife would be able to identify. The photo is an honest picture of how I often felt and how he was bent.

Calib’s thorn-in-the-flesh, we would later learn, is an irritating little beast named ADHD. To be fair, almost every little boy has moments of inattention or overexcitement. I once was among those who discredited the disorder as an excuse for poor parenting or the result of too much screen time. While I wouldn’t dismiss that possibility out of hand, my wife and I could see we were doing the best we could, yet he struggled to focus and get it together, especially in school.

There are an overabundance of distractions in our day-to-day life, notably digital. With ADHD, however, the tendency toward distraction can be triggered by anything; digital devices, interestingly, often provide an opportunity to focus. External distractions, however, abound. A two-minute task such as getting dressed in the morning, unsupervised, may take twenty minutes, or may never happen at all without oversight, since the die cast superhero figures need to be setup in a row on the bed frame, and, hey, is that a dog outside? I love dogs. Where is my dog book? I don’t see it, but this other one has stickers in the back and etc., etc., until mom or dad return to find that, while many steps have been taken over the last half-hour, not one of them was in the right direction. Make this a daily occurrence for multiple tasks and you’ll have some idea of the struggle.

That’s the AD side of the coin. The HD, in Calib, manifests itself, at its peak, as a surplus of supercharged joie de vivre, as in, life is a musical comedy, he’s the leading man, and dad is proving a tough crowd; no matter, I’ll just sing louder and see if I can break him. He can put on an entertaining show, but it makes for a long day. I once attempted, at bedtime, to almost hypnotize him into standing still and quiet. While he made a valiant attempt, the resemblance to an animated rocket shaking under the pressure either to launch or explode was jarring.

Put the two of these together, AD and HD, and it’s difficult for the afflicted to get anything done. It became clear after some time that he, and we, needed help. If he wasn’t focusing in school, he was using the environment as his stand-up stage, his classmates a captive club audience. Such a bright shade of positive energy may not sound like the worst one could imagine, but he simply wasn’t capable of reining it in. After a diagnosis by both a psychologist and physician, it was determined he was a candidate for medication. Once the dosage was pinpointed, the change was almost immediate with no negative side effects. Straight As and no more notes or calls from the teacher.

I don’t necessarily consider it a miracle and wouldn’t stand in front of a camera to laud the benefits of medication, but it proved an enormous help for the time he has to spend in a classroom. You can’t and shouldn’t medicate 24/7, however, at least not in our case. For the moments in between, which is typically with us at home, my patience is still significantly tested. As with his condition, it remains at times hard for me to rein in my impatience.

For those who attempt it, getting kids ready for church on Sunday mornings is its own special challenge. Success or failure hinges on getting everyone out the door and into the van at a reasonable time with lofty aspirations of arriving no more than fashionably late. It’s tough, but it can be done. First things first, though. At breakfast recently, I responded to his antics with severity rather than understanding and lost my cool with him more than once, much to my wife’s, and his, displeasure. As justified as I felt at the moment, and though there was resolution, albeit imperfect, self-talk, as it’s known, judged me a terrible father. It often does.

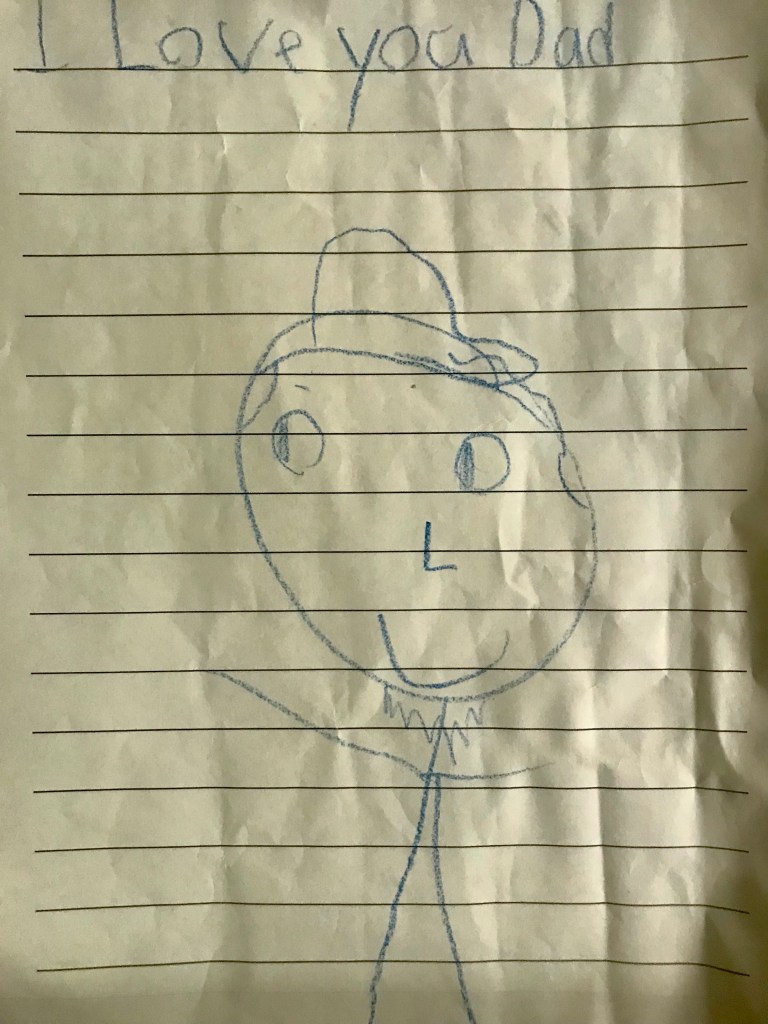

By the time service was finished, he stepped into the van and passed forward to me from the back his most recent masterpiece. On it were the words “I love you Dad” and his best impression of me, complete with baseball cap and facial hair, not to mention a smile on my face. Jenny, my wife, also received a similar image from his time at camp a week before. Though it was intended as an opportunity to write a letter to mom and dad, he took the artistic route and penned a simple picture of her surrounded by hearts. In any event, his portrait of me didn’t reflect in the slightest what I saw of myself that morning, but it was a revelation to me that the mirror our kids unwittingly hold up to us seldom reveals how they actually see us.

Beneath the ADHD that frustrates and tries my patience almost daily is simply a kid who loves his mom, wants to please his dad, and who would rather spend his camp money on gifts for each of us than on himself. To that, I say thank God for the patience and forgiveness of our children. Without it, we would not see ourselves as they do and might not have the courage as parents to get back up and try again.