“Somebody donated these to the bookstore. I thought you might find a use for them.”

John Lottinville, one of several Friends of the Library board members and bookstore volunteers, reached across my office desk and handed me a set of old NASA prints of the Apollo 12 mission, released years ago and of no special value to anyone but a collector of early NASA memorabilia. John himself was a retired lawyer for the Johnson Space Center and retained a lingering esteem for the program, having met plenty of astronauts himself during his career, including those featured in the prints. I thanked him for the thought and took a closer look at his acquisition: over half a dozen cardstock prints each slightly larger than a legal-sized sheet of paper, featuring photos of various moments of the mission that followed the historic first landing.

Among the three crew members, which included mission commander Pete Conrad and command module pilot Dick Gordon, was lunar module pilot Al Bean — a wholly uninspiring name for a historical figure, in my humble opinion. He did, however, bear the distinction of having been the fourth man to set foot on the moon and was tied to Ted Freeman, whose memorial library I had, at the time, been managing for a few years.

“Ted Freeman“ isn’t a name many outside of NASA circles or fandom would recognize. Prior to 2004, I didn’t either. That was the year I began my professional career as a public librarian in Clear Lake, the southeast corner of Houston, in an updated facility named after an astronaut who, tragically, never had the chance to ride a rocket. It’s likely he would have been among those who would eventually find himself venturing into space or bouncing and gliding across the bright lunar surface, were it not for a bird strike that forced him to make the valiant yet fateful decision to avoid crashing his T-38 into residences below and veer off into open ground, undoubtedly saving lives in the process — save his own, that is.

Freeman and Bean joined NASA as a part of Astronaut Group 3, which included, among others, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins. As I studied the prints, I recalled this connection between the two of them. It then occurred to me that Bean was one of the few Apollo astronauts still living, and, as it just so happened, residing right here in the Bayou City.

I had found it fruitless in recent months to solicit a visit by an Apollo astronaut for the library’s 50th anniversary. Appearance fees for any of the most recognizable names are almost as lofty as the altitudes they reached during their missions, I learned, and public libraries are hardly blessed with the budgets of the many energy companies that envelop Houston. “Maybe I can’t persuade them to visit,” I thought, “but perhaps there’s another way to give the public at this library a closer connection to the program that began right here in their own neighborhood.”

I pivoted over to the computer, searched, and found that Bean, as many did, maintained a website, much of it featuring his art, a hobby he enthusiastically took up following his awe-inspiring trip to the moon. Clicking on the “contact” section, I punched in the details, noting Mr. Bean’s link to Freeman as a “classmate,” mentioning the acquired prints, and humbly requesting just a single autograph on only one of them so that they could be placed on permanent display for the public. My expectation after submitting the message was, in all honesty, to receive a response from an aide or site manager weeks later stating that Mr. Bean appreciates the request but would respectfully have to decline. I had read enough such polite refusals to expect nothing less.

Once and a while, however, persistence pays off. “Ask and ye shall receive.” A mere hour later, in my email inbox appeared a new message. Figuring it to be either an automated or stale, noncommittal response, I clicked, opened, and read the following casual reply as if the sender were texting a familiar friend:

Jim,

Can you send a picture of the prints?

Al

Now, few accomplishments top a trip to the moon. The first to attempt the journey were a uniquely capable breed of individuals who willingly risked their very lives to travel faster and farther than any humans in history. If any could be forgiven for possessing even a dim shade of an ego, they’d likely qualify. Yet, here I was, having been offered the special courtesy of a swift answer not by an assistant or secretary, but by the very astronaut who stepped out onto the lunar surface himself.

After taking a moment to register my shock that I was now engaged in an unexpectedly comfortable email conversation with a moonwalker, I gushingly replied with gratitude and haste, attaching pics of each and every print, offering to send them with a postage-paid return envelope. Within minutes, he again replied that he would be glad to accept my request and to send them his way to the provided address.

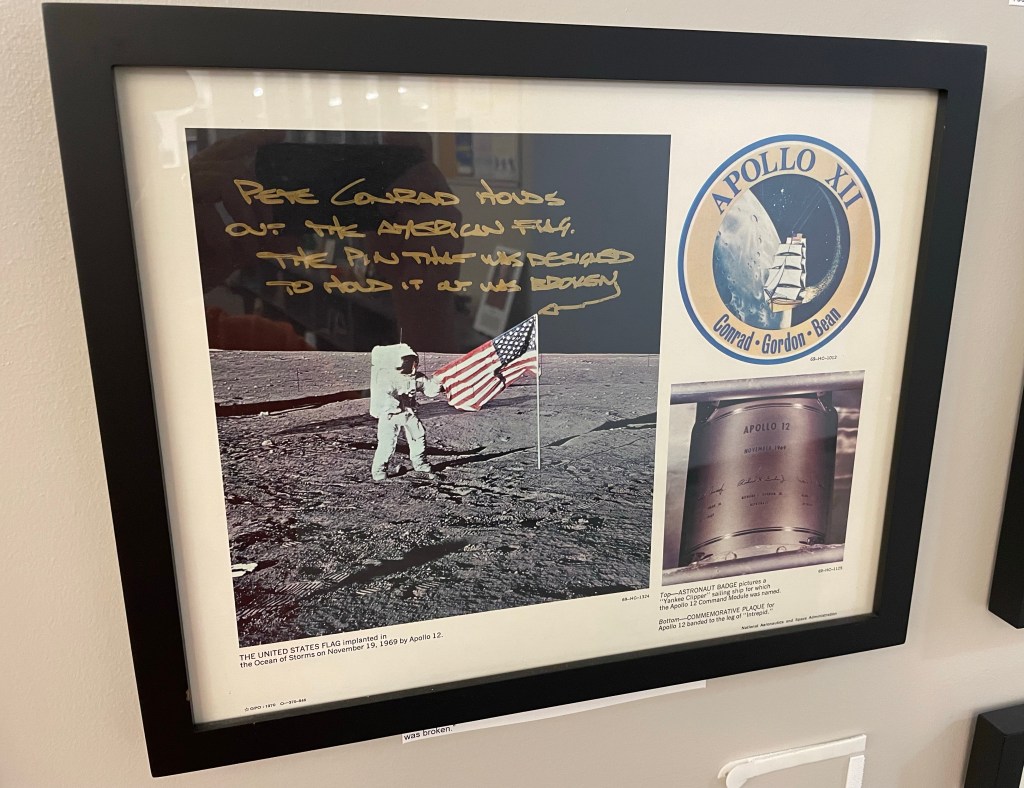

The following morning, I wasted no time and sent them on. I waited only a week for the large, prepaid envelope to return to me. Sitting at my desk, I carefully sliced open the narrow end expecting to find his autograph on the one print featuring his official NASA photograph with his crewmates. In this, I was not disappointed. But as I removed and laid out each of the remaining prints, I was delighted to find that Al had decided to do me one better.

On each of the others, featuring a photograph of his and Conrad’s activity on the lunar surface, he detailed by his own hand and in as much space as the print would allow what he and his commander were doing in the image at that specific frozen moment in time. I marveled at what I was seeing. I took great pleasure in realizing what a staggering gift this was to this library and how it would further cement its significant, local connection to the space program. Bean had been beyond gracious to share these with his deceased colleague’s memorial building, and I couldn’t have been happier.

Bean passed away a few short years after this gift to the library. Today, these signed prints remain on display on the second floor for the public to enjoy, right next to an American flag carried into space on Gemini V by his friend and Apollo 12 commander, Pete Conrad. I never had another encounter with an Apollo astronaut, but it remains one of my favorite stories during my time managing the Freeman Library.

Living and working in Clear Lake, you run into plenty of NASA professionals, all with their own unique jobs but all with the singular goal of sustaining man’s presence in space. I became a fan not long after becoming employed by the county library and learning all I could about the first full decade of the program in the 60s. The astronauts themselves, both past and present, walk among us here, and I’ve found few of them carry themselves as if celebrities. I once paid my rent to a former astronaut, attended church with another, and even had occasional interactions with one who received an embarrassing share of national publicity for an unfortunate personal mistake. It’s easy to forget those few among us tasked with such important, high-profile jobs that deserve the title of “missions” also shop for groceries, pay bills, and argue with their teenagers, just like the rest of us.

Next year, after over 50 years, four crewmates in many ways just like the rest of us will return to the same moon Al Bean walked upon, and I couldn’t be more thrilled. The first landing is one of the only events in all of recorded history that drew the attention of the entire world. It’s my hope that once again, for at least a moment, there will be peace on earth as all eyes are fixed on the moon above.

I’ve shared with several that I’d be happy to sweep the floors at JSC just to say I worked for NASA. I continue to be inspired by their efforts to explore, take risks, and challenge what’s possible. Alas, they’ve never called to offer a job, but I’ve nonetheless been grateful to have worked in the library that serves the NASA community. I’ll likely in years to come bore my grandchildren and great grandchildren with the story of my email conversation with the fourth man to set foot on the moon.