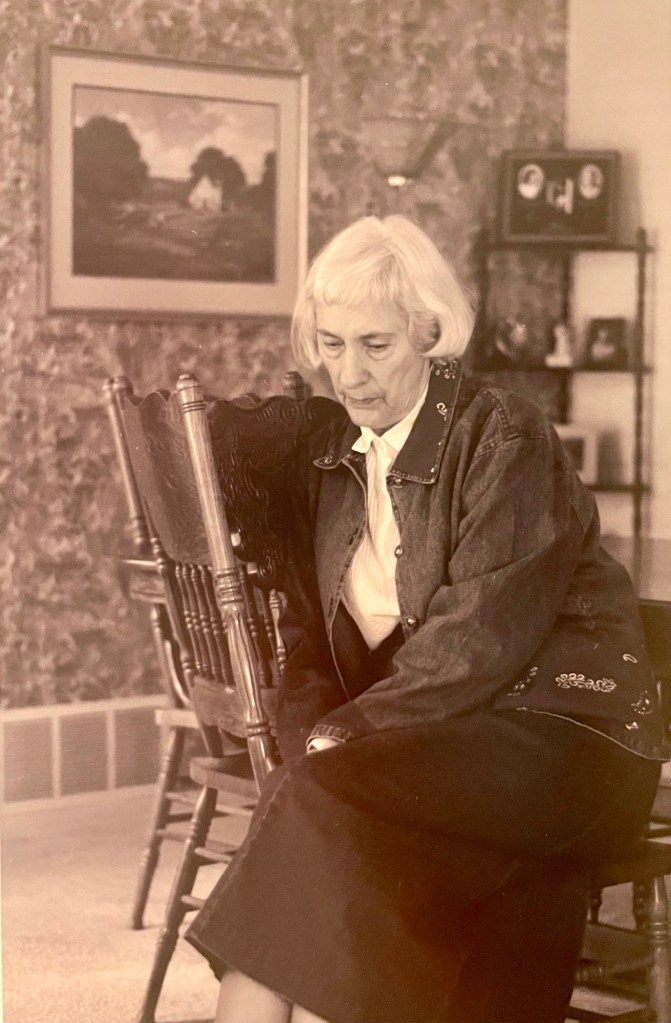

I’ve sought to say something poignant and meaningful about my grandmother’s passing at 95 yesterday evening, yet I’ve struggled to do so. I’ve thought at length about my grandfather’s death a few months ago, and I admit most of my tears were shed then, in part for both of them in anticipation of hers as well as she continued to decline. So, the deepest grief has, in a sense, given way instead to observation of how she chose to finish her final hours.

My college philosophy professor, arguably the most challenging instructor on campus from which to earn an ‘A,’ said to each of his students at the outset concerning the subject, “I intend to teach you two things: 1) how to live with people, and 2) how to die alone.” My fellow students and I likely pretended to understand what he meant, though we wouldn’t have guessed that would have been the way to begin such a course. I have a better appreciation for it, however, 25 years since, and I think my grandmother, who was not a student of philosophy, probably had a better understanding at the end than almost anyone I know.

I’ve already written about the memories and the legacy she left to me. These last few weeks and months, however, she left behind something quite different. Contrasted with many of us who do our best to avoid the subject of death or thoughts of it, especially the inevitability of our own, my grandmother faced it bravely, even with anticipation. This isn’t to say it was rooted in a depressive state of mind. No, it was born of hope, built for decades upon a solid foundation of what she believed, that this isn’t the end, that all was simply preparation for these final days and what awaited her after.

My parents, both having finished their working life in the care of others in hospice, know well when the end is near, having sat at the bedsides of innumerable individuals. They know well that not all welcome the end, that it can be a time of great anguish for the dying, and not merely for any physical pains. Fear is most powerful for those who have distracted their thoughts, consciously or not, far from any considerations of the end. Witnessing this can be just as troubling for any observer as it is for the one forced, finally, to face it.

Not so for my grandmother. And I’m glad for this and for what my parents have shared with me, since I was not able to be present. Not only did she share feebly from her bed that both her partner of 77 years, my Papaw, and her son, Jimmy, were present, but expressed joy — yes, joy — when hearing that she would probably become unresponsive before too much longer, indicating to her that she was close. The only comparison I have is our children in anticipation of a trip, just prior to stepping onto a plane for departure. She couldn’t wait. Her faith in God and the promises she cherished all her life prepared her for the transition.

I have no idea when my own end will arrive. I have significant doubts I’ll make it to 95, if for no other reason than I don’t believe I’ve taken quite as good care of myself as my grandmother. But I do hope, in the years to come, I would have learned as well as her how to live with others and how to die not simply alone but well.

Death does not have to be a fearful event. It can, and, I might argue, should be beautiful and meaningful. This was the final legacy my grandmother left me.