Aging sharpens perspective even as it dulls the mind.

Author: dimaphaedos

Transition

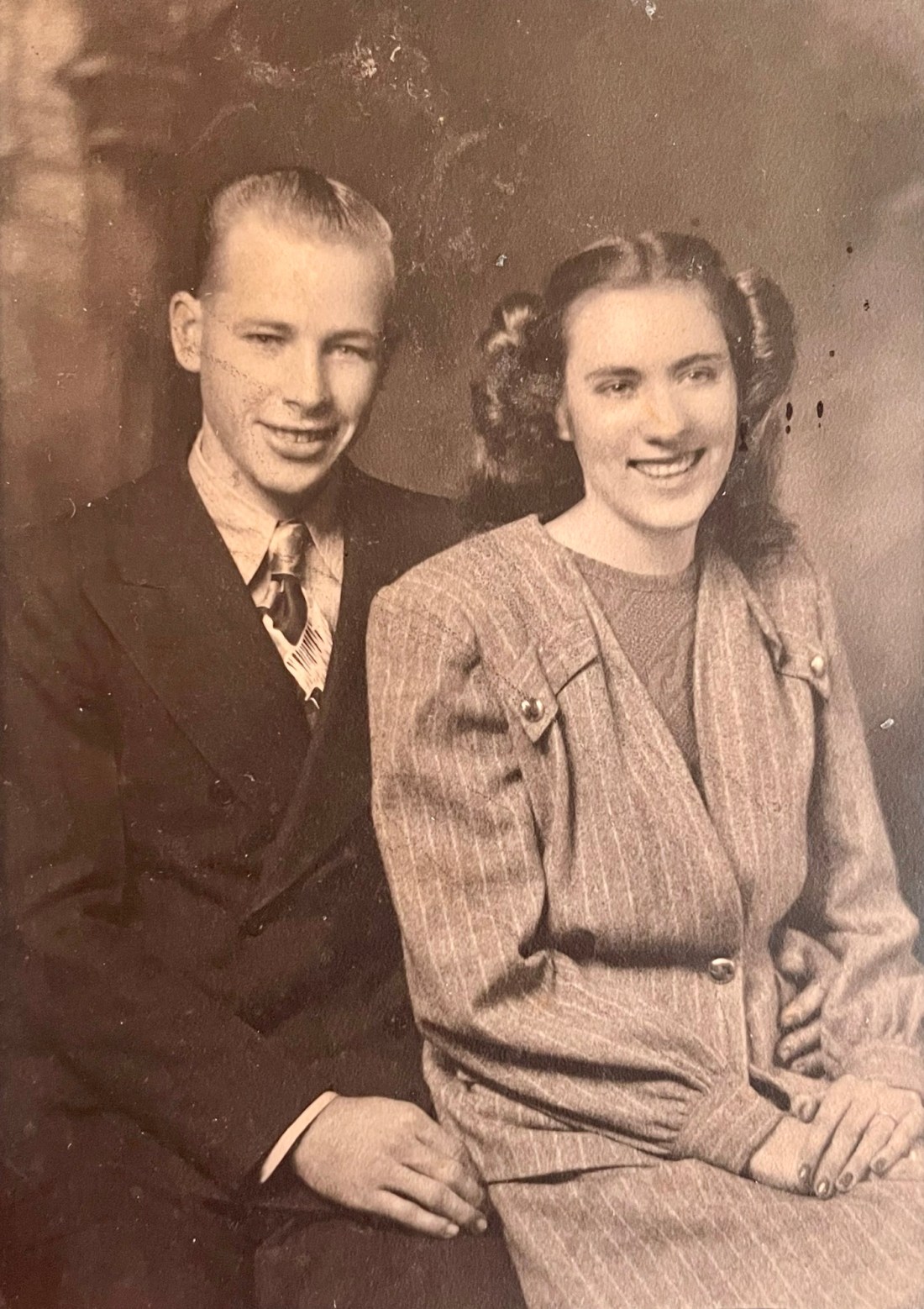

I’ve learned to place little stock in 5, 10, or 20 year projections about where one might end up in life.

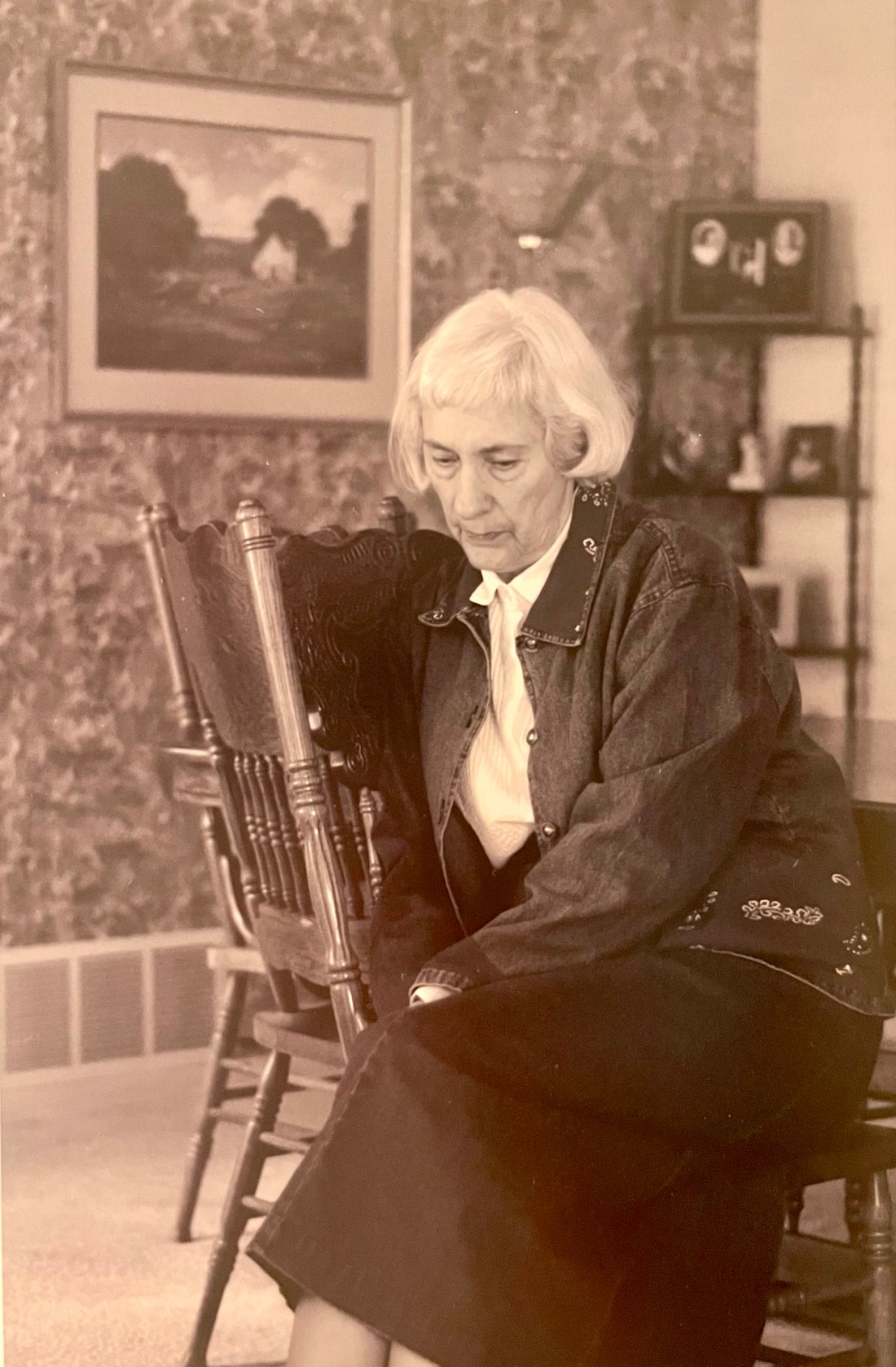

Dying Well

Contrasted with many of us who do our best to avoid the subject of death or thoughts of it, especially the inevitability of our own, my grandmother faced it bravely, even with anticipation.

Baptism

“I have no greater joy than to hear that my children are walking in the truth,” said John in his third epistle to his “spiritual” children. But it’s an easy fit for parents.

Ashes

Relief commingled with grief choked in my throat, as I held back the bitter emotions when she spoke the long-expected yet unwelcome words. “It’s over. He’s gone.”

Sweet Sixteen

It’s said that time heals all wounds, though this is no guarantee. While I was not the wounded party, we could only hope this would hold true for the trauma our children might have experienced, even as we learned to become the parents they needed, albeit imperfectly.

Reconstruction

2023 will go down as the year the warranty on my personal health expired.

Mileage

Plan and hope for the best, but be prepared for the fact that expectations you have long had for your own personal standards of success may need to be jettisoned in order to redefine what success is for your kids.

Picture of a Pandemic

More than a picture . . . it’s a critical lesson for times of trouble or misfortune. Joy is present and available if you choose it.

Legacy

I had not considered it before, but legacy, I realized, isn’t something that is necessarily left behind at the moment we pass out of this life . . .