As I removed and laid out each of the remaining prints, I was delighted to find that Al had decided to do me one better.

Author: dimaphaedos

Sisyphus

“As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.” - Proverbs 27:17

Maw

A scan of the room, sermonic words aside, was more than enough to inform that this person’s life mattered, that her time was very well-spent not in insular pursuits, as we are typically encouraged to pursue in life, especially American cultural life, but in the interest and care of others.

Past Time Pastime

It’s not always about the platform for the memories, as in this case, baseball, but about how the memories made us feel.

Immanuel

Sometimes, you just have to swallow that pill.

Trouble

As time drags on and resolutions remain absent, the wish for a satisfying conclusion can easily give way to just an end — any end — good or bad. Let’s just get this over with, please.

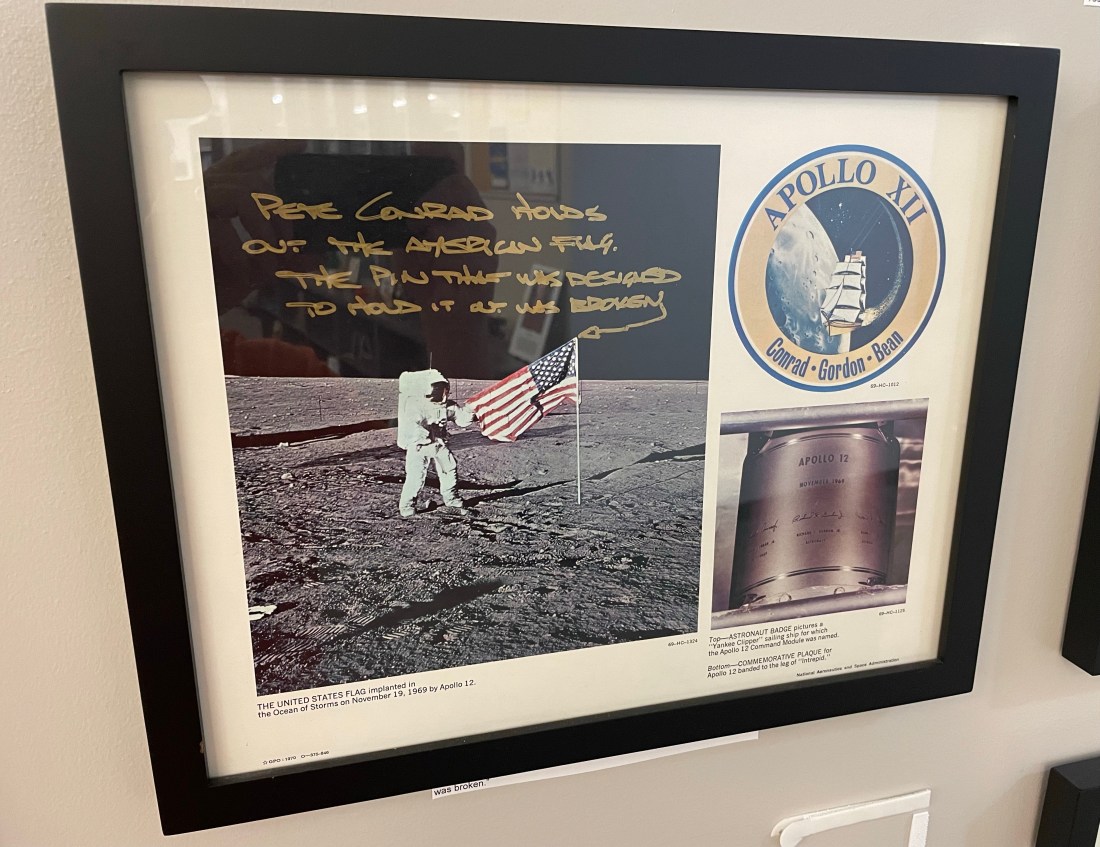

A Thousand Words

“Photography has nothing to do with cameras.” - Lucas Gentry

Heart Racing

“I believe every human has a finite number of heartbeats. I don’t intend to waste mine running around doing exercises.” - Neil Armstrong

On the Road

. . . we all likely have a great deal of stories to tell with our vehicles as a setting or, perhaps, as a participant . . .

Hope

“Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.” – Romans 12:12