Aging sharpens perspective even as it dulls the mind.

Tag: aging

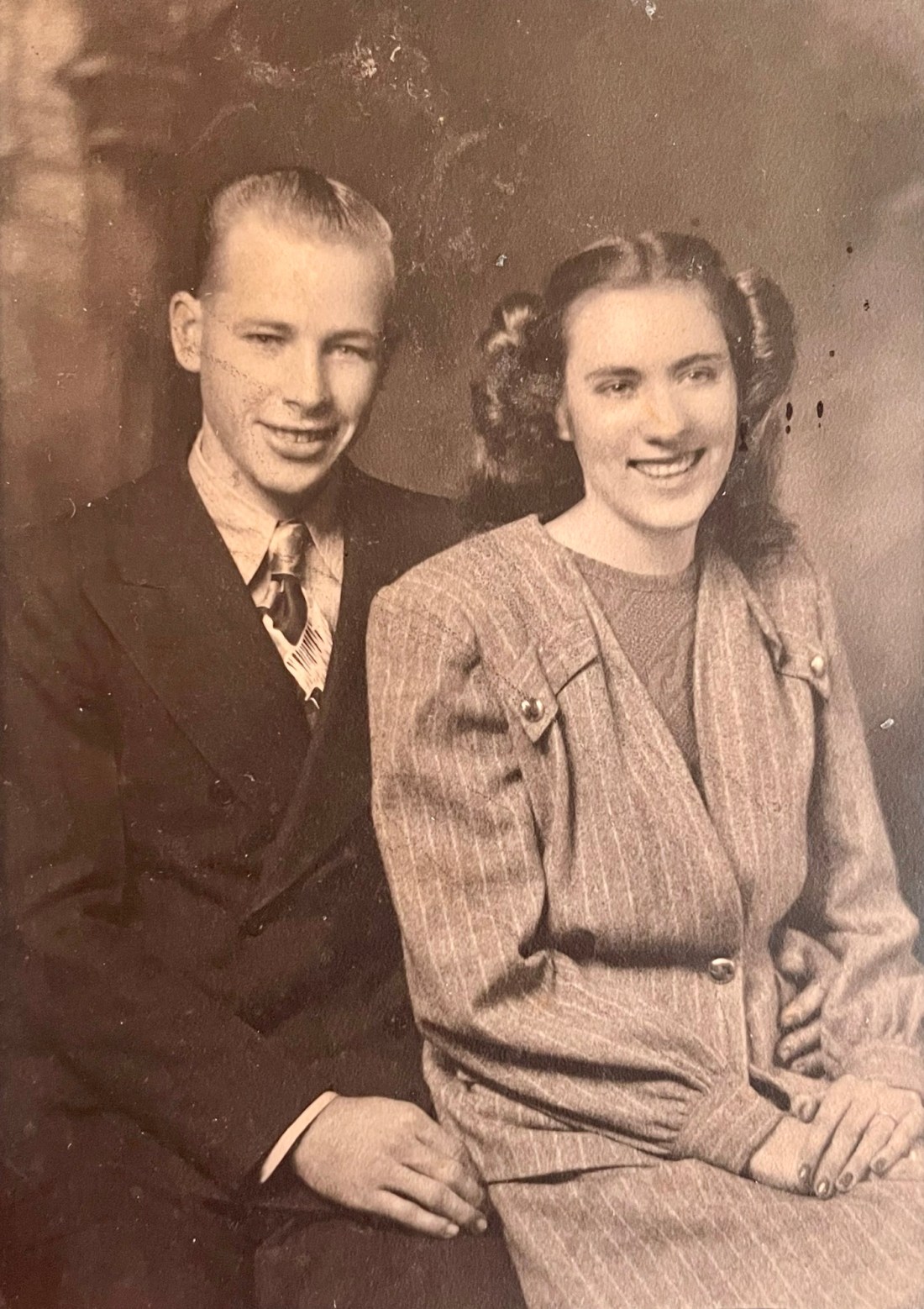

Ashes

Relief commingled with grief choked in my throat, as I held back the bitter emotions when she spoke the long-expected yet unwelcome words. “It’s over. He’s gone.”

Reconstruction

2023 will go down as the year the warranty on my personal health expired.

Maw

A scan of the room, sermonic words aside, was more than enough to inform that this person’s life mattered, that her time was very well-spent not in insular pursuits, as we are typically encouraged to pursue in life, especially American cultural life, but in the interest and care of others.

Heart Racing

“I believe every human has a finite number of heartbeats. I don’t intend to waste mine running around doing exercises.” - Neil Armstrong

Hope

“Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.” – Romans 12:12

Numbered Days

“There never seems to be enough time to do the things you want to do once you find them.”