Each new year can feel like just another number, but more often than not I’m astounded that it’s already been another year.

Tag: anniversary

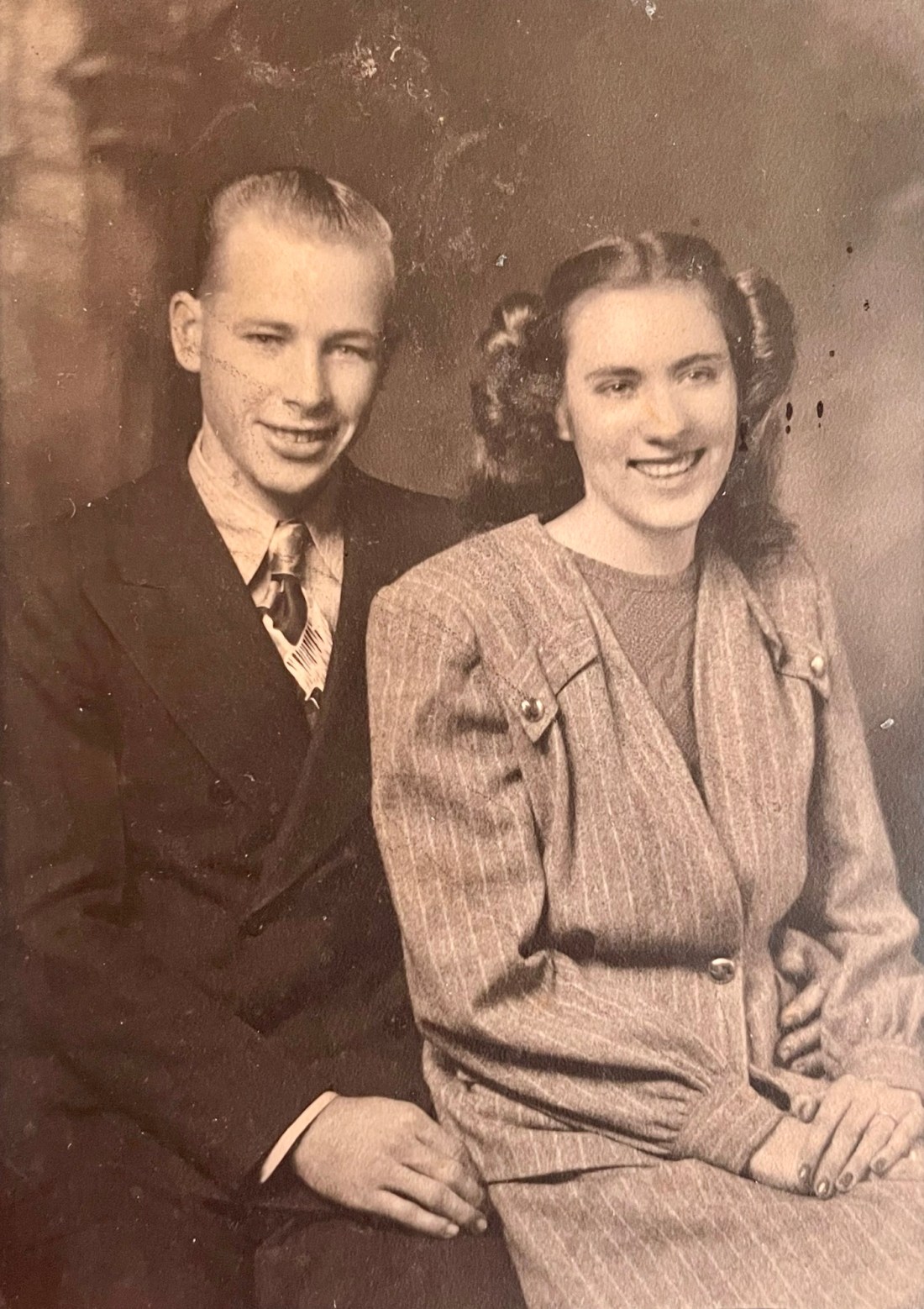

Ashes

Relief commingled with grief choked in my throat, as I held back the bitter emotions when she spoke the long-expected yet unwelcome words. “It’s over. He’s gone.”

Unqualified

“If anything is worth doing, it is worth doing badly,” wrote G.K. Chesterton.