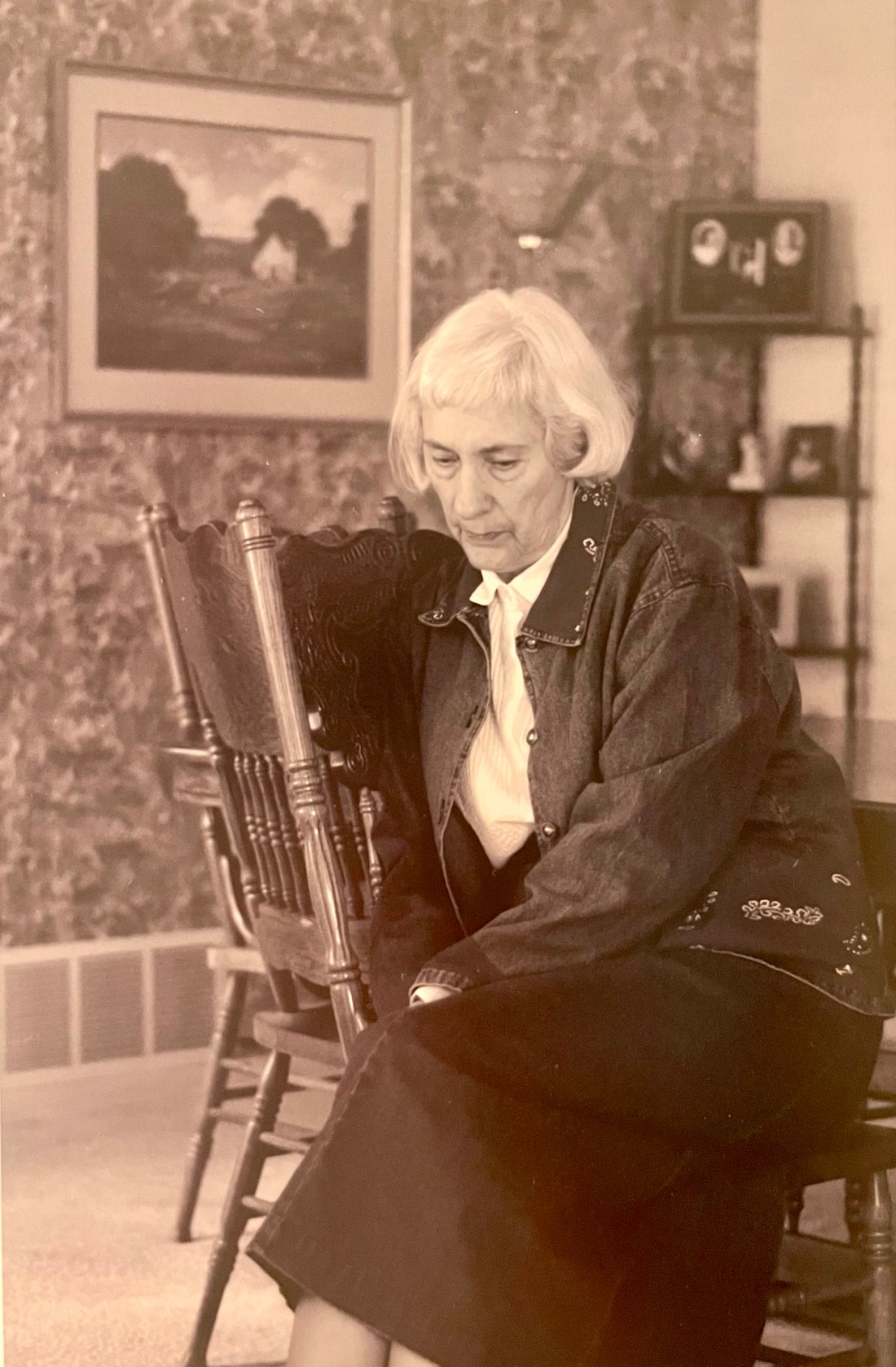

Contrasted with many of us who do our best to avoid the subject of death or thoughts of it, especially the inevitability of our own, my grandmother faced it bravely, even with anticipation.

Tag: faith

Baptism

“I have no greater joy than to hear that my children are walking in the truth,” said John in his third epistle to his “spiritual” children. But it’s an easy fit for parents.

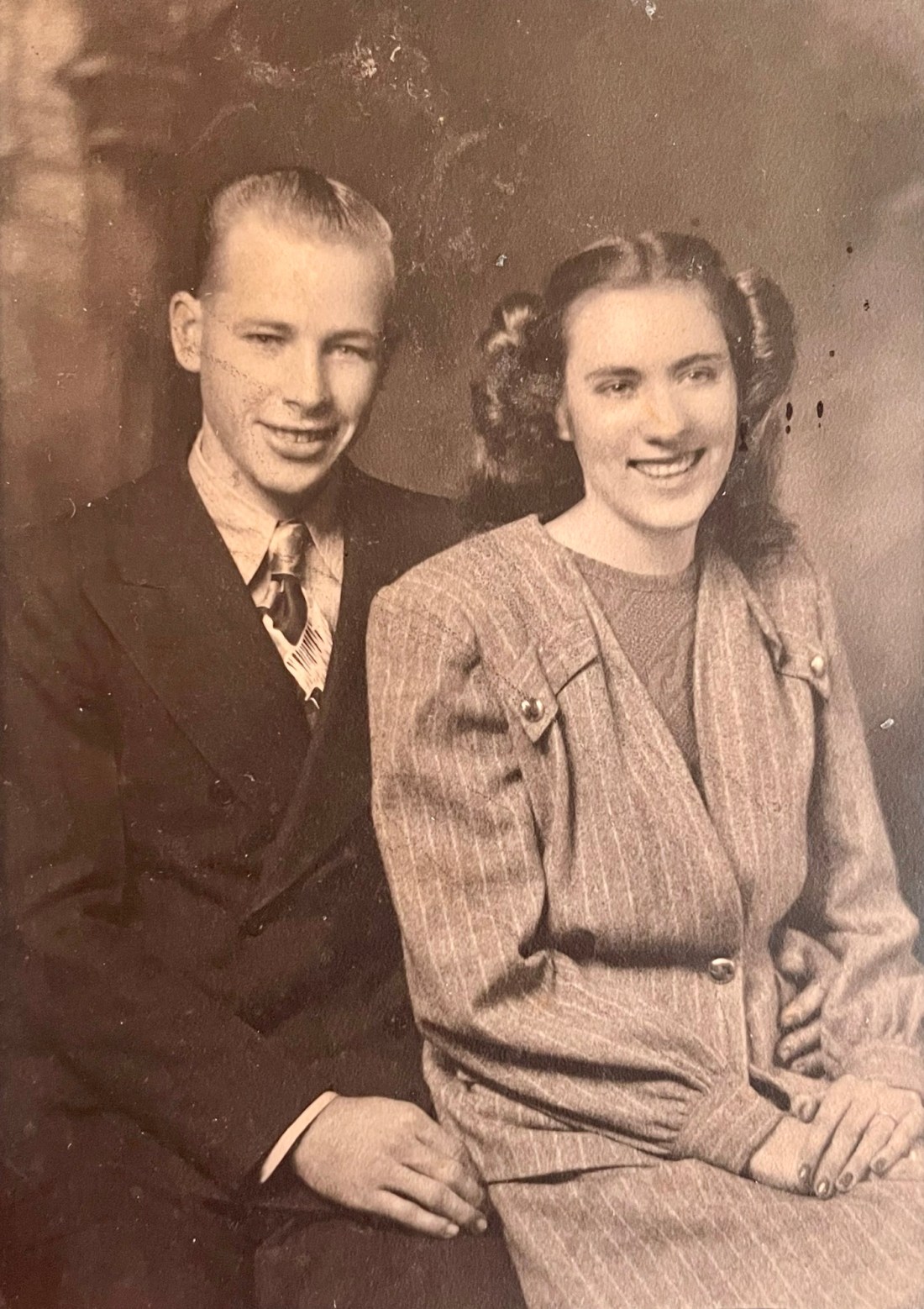

Ashes

Relief commingled with grief choked in my throat, as I held back the bitter emotions when she spoke the long-expected yet unwelcome words. “It’s over. He’s gone.”

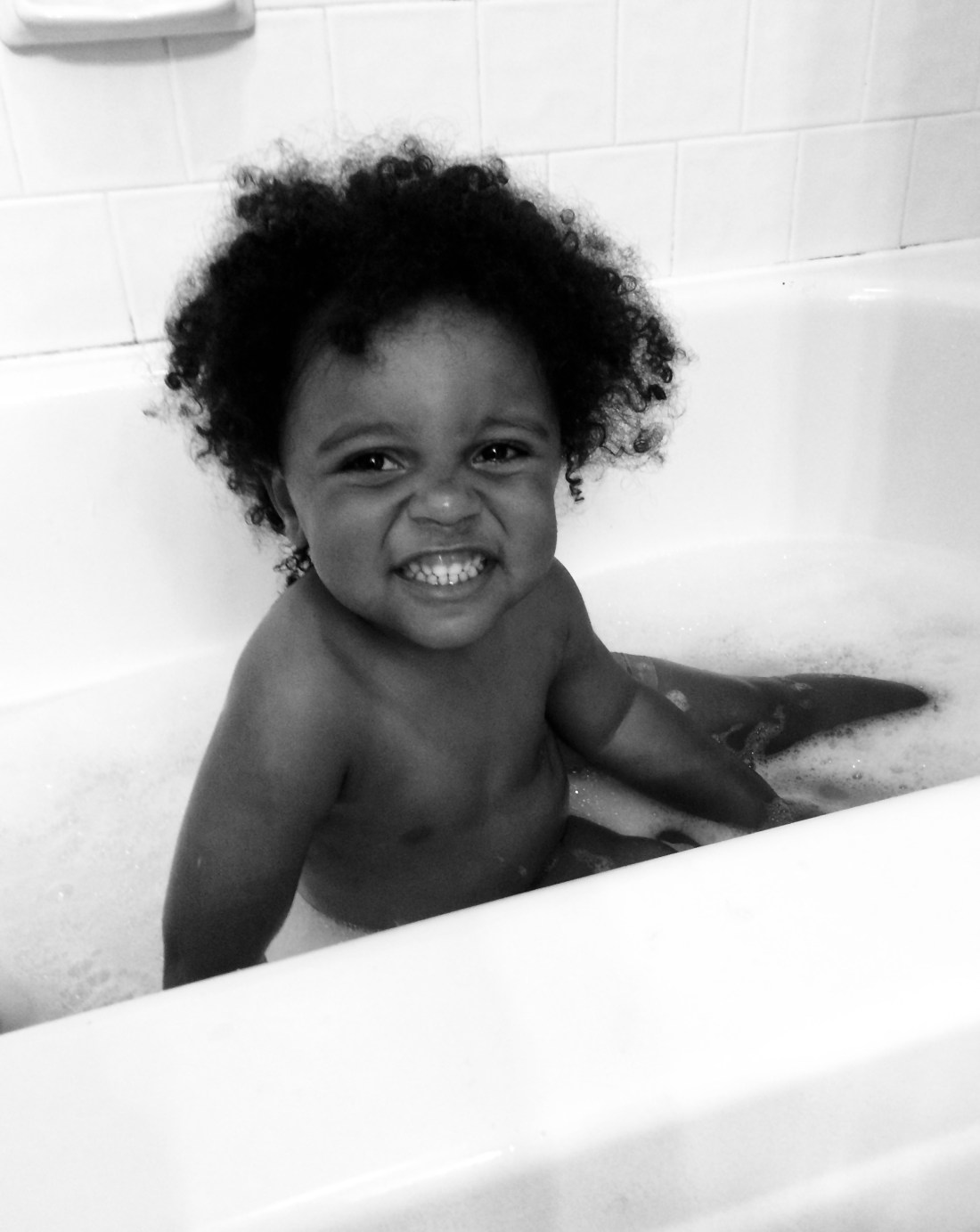

Picture of a Pandemic

More than a picture . . . it’s a critical lesson for times of trouble or misfortune. Joy is present and available if you choose it.

Immanuel

Sometimes, you just have to swallow that pill.

Trouble

As time drags on and resolutions remain absent, the wish for a satisfying conclusion can easily give way to just an end — any end — good or bad. Let’s just get this over with, please.

Hope

“Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.” – Romans 12:12

IDK

As I remarked to someone recently, it’s not that the bar is set lower. The bar is in an entirely different location . . .

Checklist

It was rapidly apparent and unmistakable to me that one of the chief aspects that was going to make parenting so challenging was the fact that I couldn't address them like a task on a to-do list.

Spring Broken

Before I knew it, the brief but cutting words shot out of my mouth like a cannon, aimed squarely and unequivocally in our child’s direction.