How does one determine the will of God? Why, in that moment, did I interpret circumstances as an indication he wanted me to stay where I was?

Tag: faith

Chapter 2: Dalhart

Plowing one endless furrow after another, Joel stole a longing glance at the cars speeding past on the adjacent road, each headed anywhere but here.

Prelude to Risk, pt. 2 (or Final Chapter)

“We have to make a decision today.”

Peace on Earth

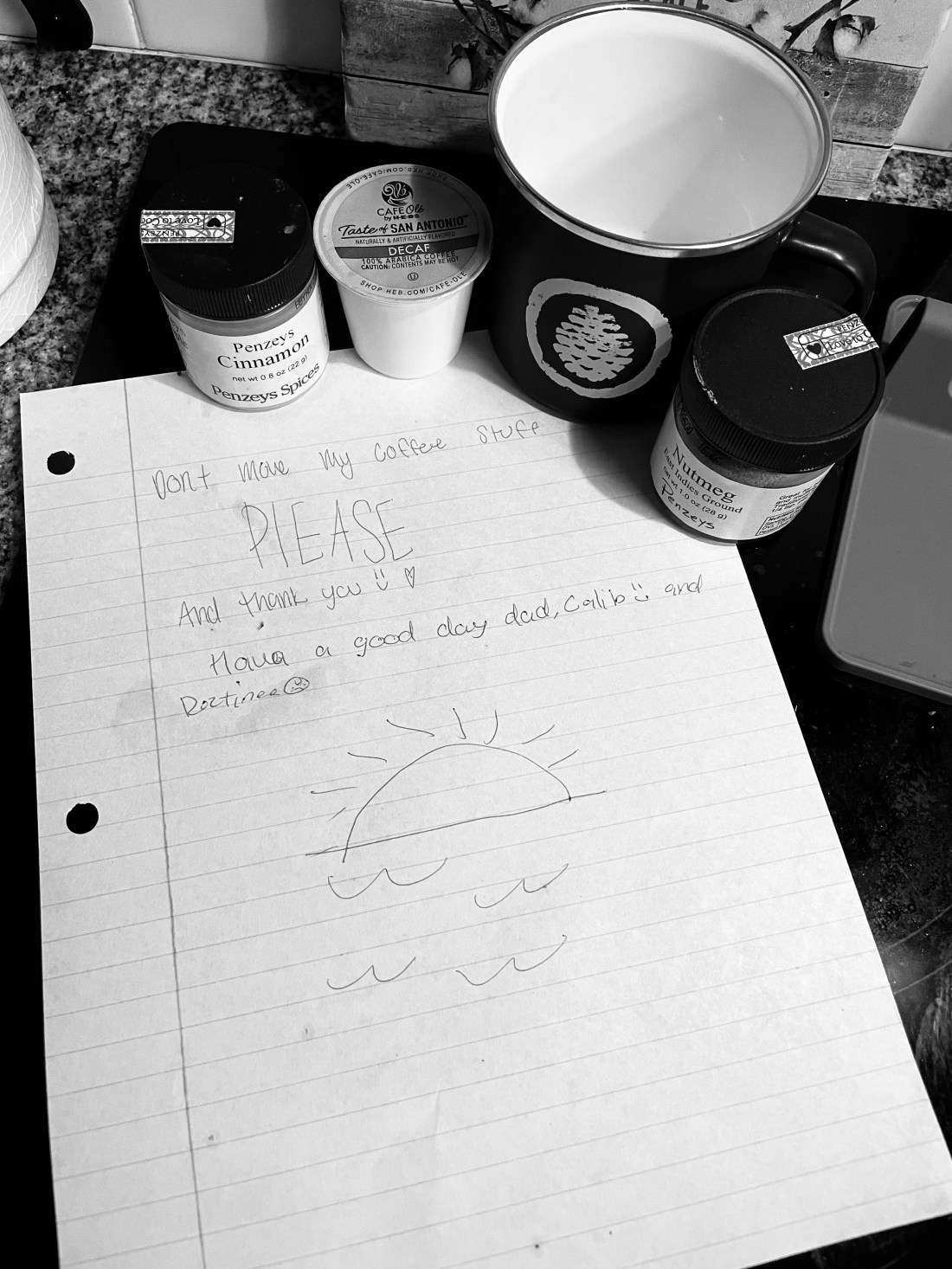

My perspective since having children has broadened significantly as to what is at one’s disposal about which to disagree passionately. Clothes, food, toys or other cherished possessions, you name it, they’ll argue over it.

Unqualified

“If anything is worth doing, it is worth doing badly,” wrote G.K. Chesterton.