“Once a kid is taken from their parent, if they didn’t have an issue before, they got one now.”

Tag: family

Gifted Time

Making a single revolution inside the mall, we spent no more than time, and this less than an hour. Pausing, we looked understandingly at one another, and left with nothing.

Chapter 2: Dalhart

Plowing one endless furrow after another, Joel stole a longing glance at the cars speeding past on the adjacent road, each headed anywhere but here.

Peace on Earth

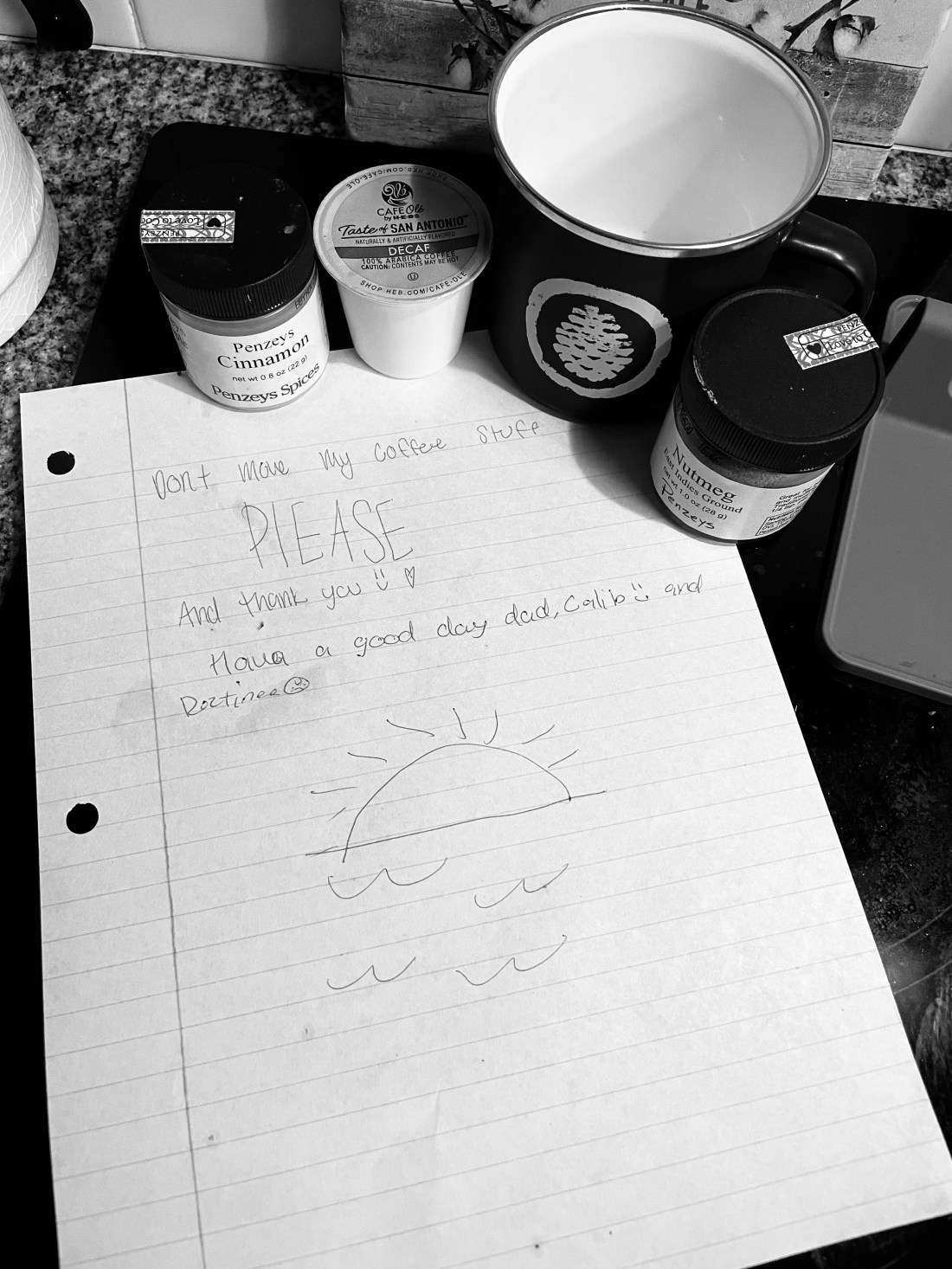

My perspective since having children has broadened significantly as to what is at one’s disposal about which to disagree passionately. Clothes, food, toys or other cherished possessions, you name it, they’ll argue over it.

Choosing Well

It’s a dilemma as a parent. We want them to have friends; we all need them. But age and experience have taught us about the pitfalls associated with the wrong associations, so to speak, and there comes a time when we simply can’t control or be present for every interaction or connection they make at school or elsewhere.

Gone Too Soon

Randy finished his life at 45.