“Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.” – Romans 12:12

Tag: parenting

IDK

As I remarked to someone recently, it’s not that the bar is set lower. The bar is in an entirely different location . . .

Checklist

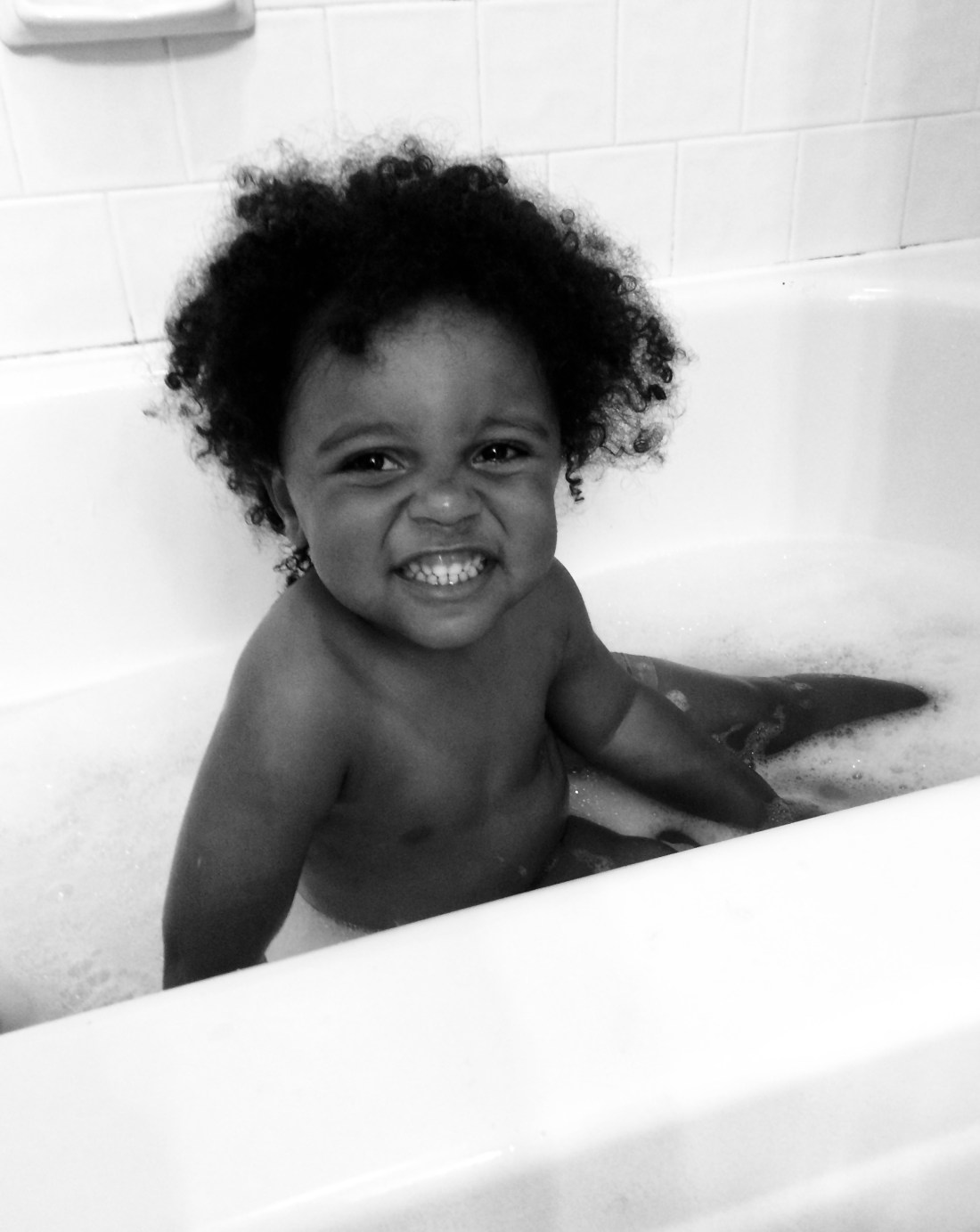

It was rapidly apparent and unmistakable to me that one of the chief aspects that was going to make parenting so challenging was the fact that I couldn't address them like a task on a to-do list.

Spring Broken

Before I knew it, the brief but cutting words shot out of my mouth like a cannon, aimed squarely and unequivocally in our child’s direction.

Animal House

“Pets are humanizing,” said James Cromwell. “They remind us we have an obligation and responsibility to preserve and nurture and care for all life.”

Paradox

“Once a kid is taken from their parent, if they didn’t have an issue before, they got one now.”

One Turn

How does one determine the will of God? Why, in that moment, did I interpret circumstances as an indication he wanted me to stay where I was?

Prelude to Risk, pt. 2 (or Final Chapter)

“We have to make a decision today.”

Peace on Earth

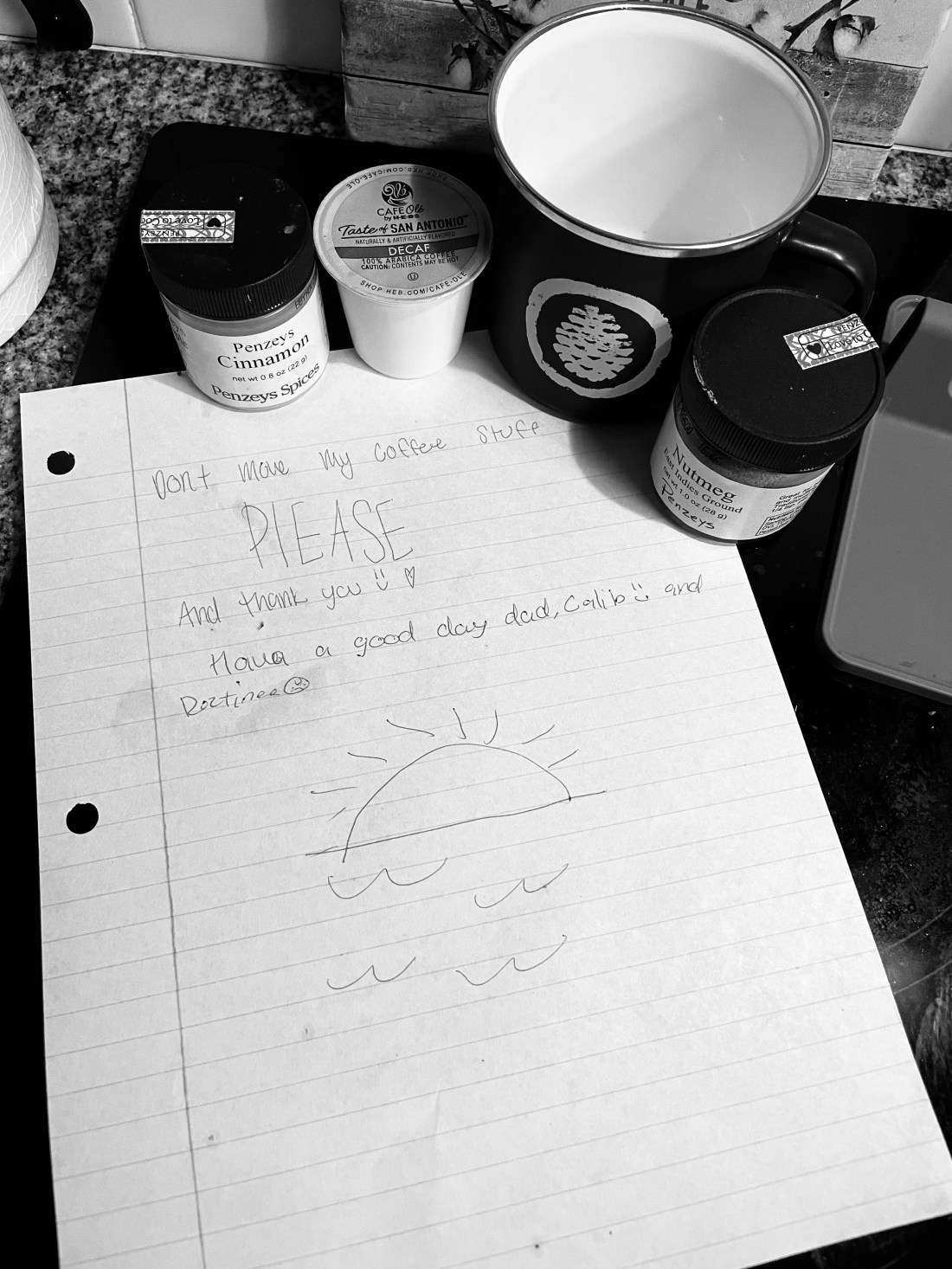

My perspective since having children has broadened significantly as to what is at one’s disposal about which to disagree passionately. Clothes, food, toys or other cherished possessions, you name it, they’ll argue over it.

Unqualified

“If anything is worth doing, it is worth doing badly,” wrote G.K. Chesterton.