Down below, where gravity binds us to the earth, it’s easy to feel important when you’re blind to the big picture. Far above, however, every self-important person on the ground disappears.

Tag: parenting

Screen Time

We all take for granted that each of us now carry in our pockets a tool far and away more advanced and complex than the earthshaking machines that sent men to the moon. With that kind of personal power, we all know there’s no going back, regardless of the extremity of any downsides discovered since.

Headlines

“Why would I bring a child into this screwed-up world?” the thought goes.

Choosing Well

It’s a dilemma as a parent. We want them to have friends; we all need them. But age and experience have taught us about the pitfalls associated with the wrong associations, so to speak, and there comes a time when we simply can’t control or be present for every interaction or connection they make at school or elsewhere.

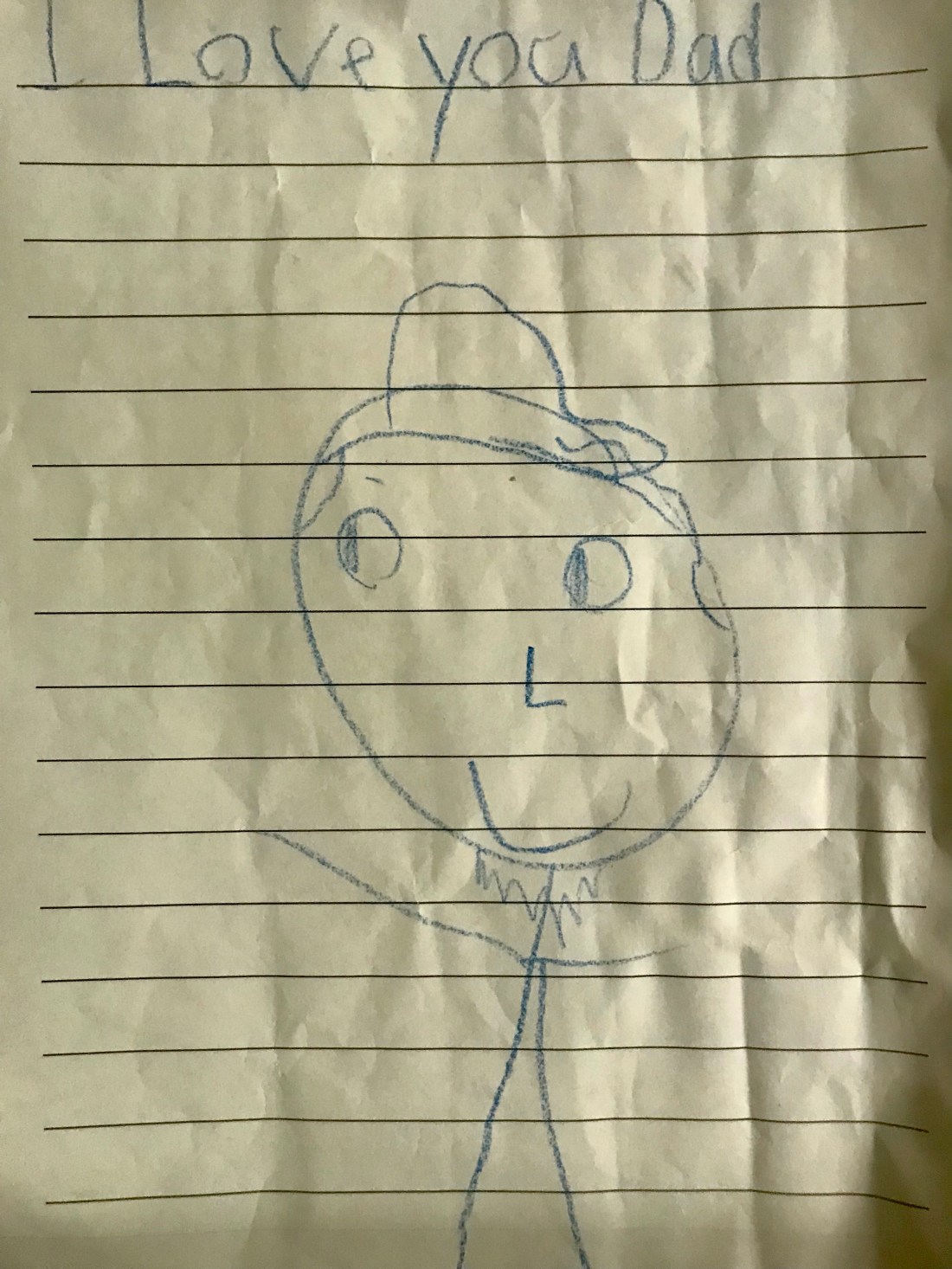

Paper Mirror

If you want to get to know yourself better, have kids. Contrary to popular belief, they don’t enter the world naked. They arrive equipped with a figurative outward-facing mirror designed to reveal to you and your spouse both your best and your worst characteristics.

Numbered Days

“There never seems to be enough time to do the things you want to do once you find them.”

What if?

As I drove the first few hours of the change, the sudden diversion in plans brought the question to mind: “What would I be doing if I didn’t have kids?”