I get myself in all kinds of trouble when I ditch this attitude, and it’s often a sign that I need to stop for the day.

Tag: patience

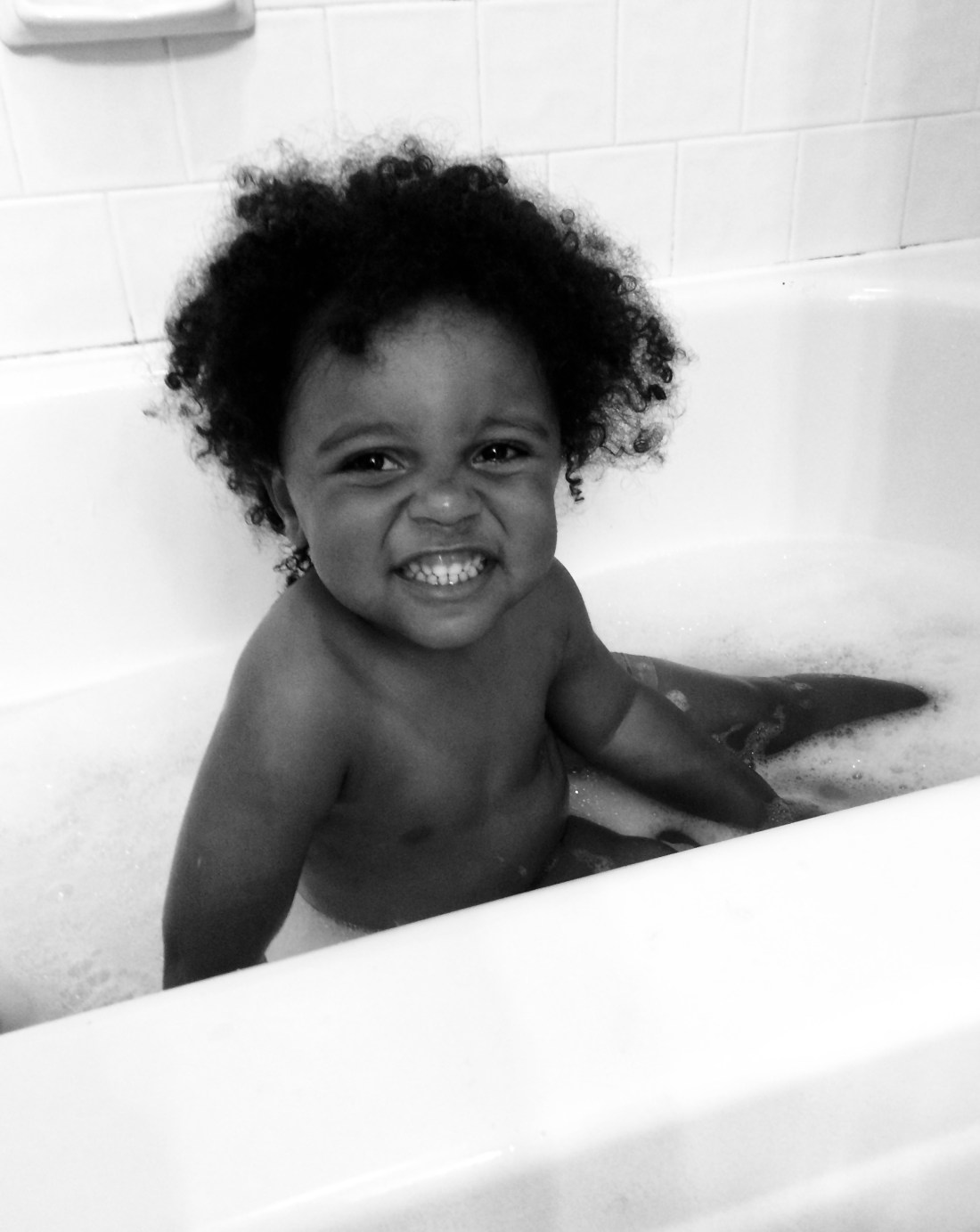

Baptism

“I have no greater joy than to hear that my children are walking in the truth,” said John in his third epistle to his “spiritual” children. But it’s an easy fit for parents.

Immanuel

Sometimes, you just have to swallow that pill.

Trouble

As time drags on and resolutions remain absent, the wish for a satisfying conclusion can easily give way to just an end — any end — good or bad. Let’s just get this over with, please.

Hope

“Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer.” – Romans 12:12

IDK

As I remarked to someone recently, it’s not that the bar is set lower. The bar is in an entirely different location . . .

Checklist

It was rapidly apparent and unmistakable to me that one of the chief aspects that was going to make parenting so challenging was the fact that I couldn't address them like a task on a to-do list.

Spring Broken

Before I knew it, the brief but cutting words shot out of my mouth like a cannon, aimed squarely and unequivocally in our child’s direction.

One Turn

How does one determine the will of God? Why, in that moment, did I interpret circumstances as an indication he wanted me to stay where I was?

Chapter 2: Dalhart

Plowing one endless furrow after another, Joel stole a longing glance at the cars speeding past on the adjacent road, each headed anywhere but here.