“We have to make a decision today.”

Tag: patience

Unqualified

“If anything is worth doing, it is worth doing badly,” wrote G.K. Chesterton.

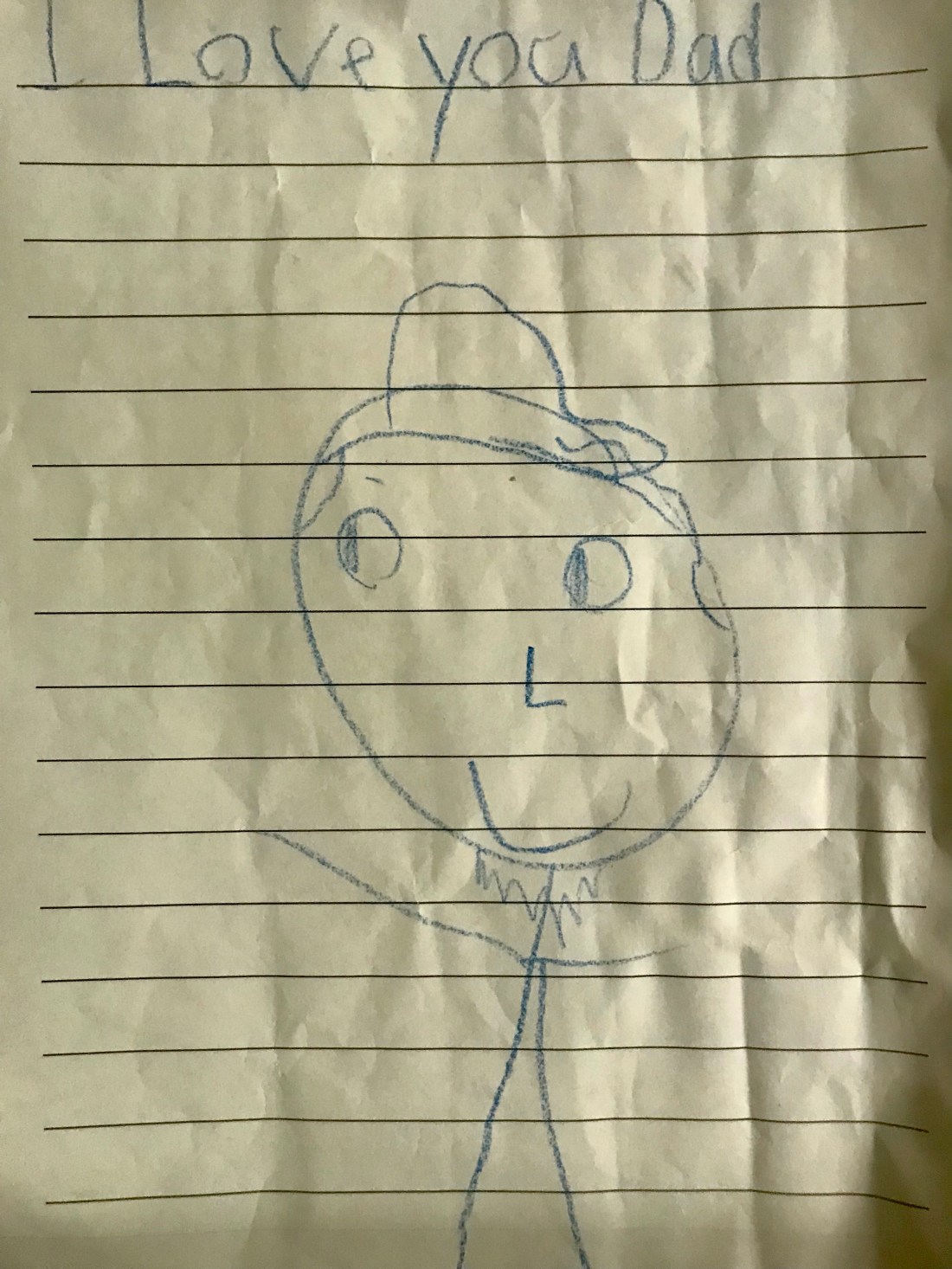

Paper Mirror

If you want to get to know yourself better, have kids. Contrary to popular belief, they don’t enter the world naked. They arrive equipped with a figurative outward-facing mirror designed to reveal to you and your spouse both your best and your worst characteristics.