Once upon a time, there was a binder in the branch manager’s office of the public library.

Tag: public librarian

Spring Broken

Before I knew it, the brief but cutting words shot out of my mouth like a cannon, aimed squarely and unequivocally in our child’s direction.

One Turn

How does one determine the will of God? Why, in that moment, did I interpret circumstances as an indication he wanted me to stay where I was?

Chapter 2: Dalhart

Plowing one endless furrow after another, Joel stole a longing glance at the cars speeding past on the adjacent road, each headed anywhere but here.

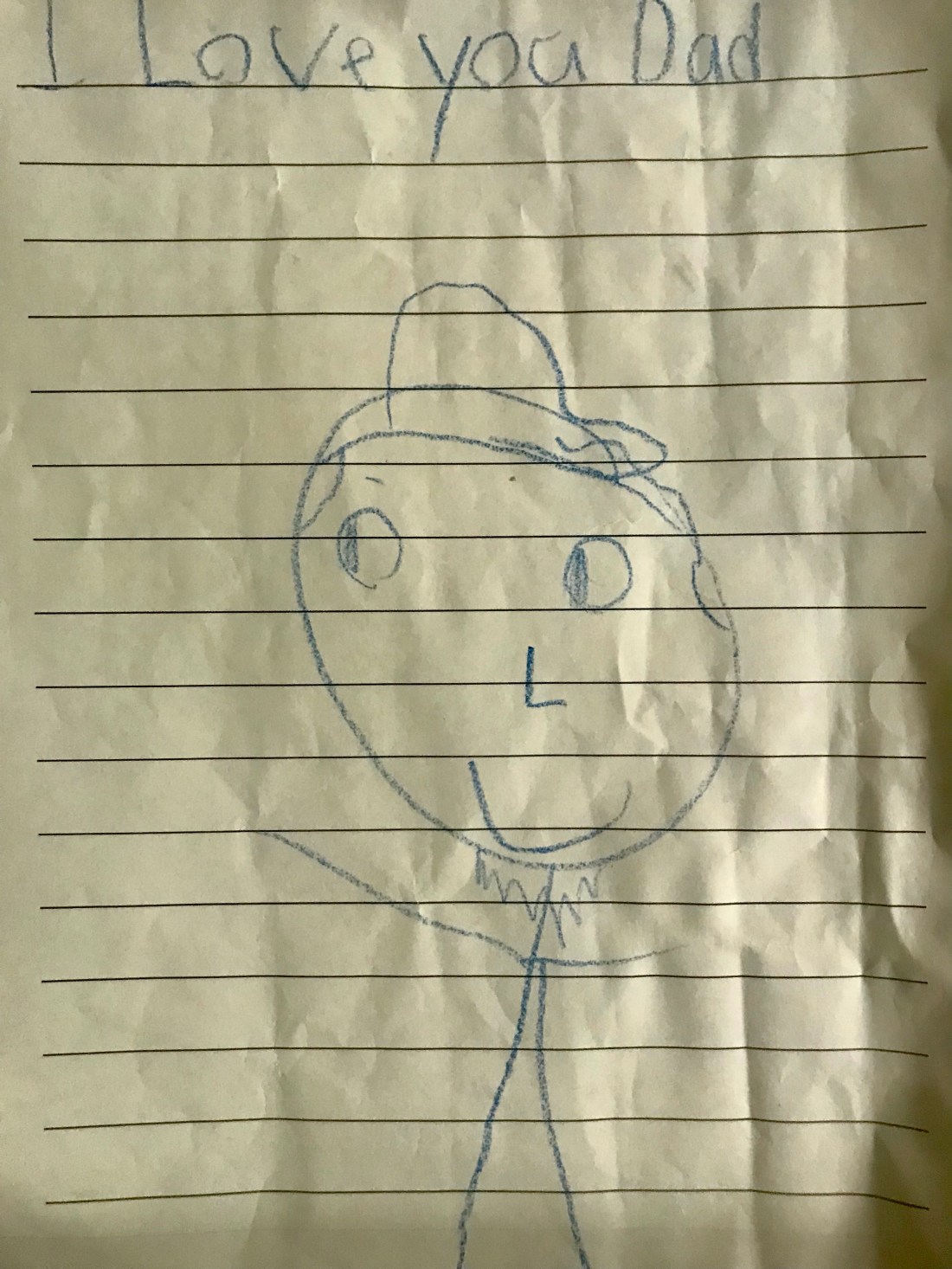

Paper Mirror

If you want to get to know yourself better, have kids. Contrary to popular belief, they don’t enter the world naked. They arrive equipped with a figurative outward-facing mirror designed to reveal to you and your spouse both your best and your worst characteristics.